Feature Story

Protecting our future health

UBC researchers are on a mission to understand how biological, social, and environmental factors interact to make us more susceptible to climate change. Their findings could hold the key to better health for everyone — starting with our most at-risk communities.

A few summers ago, during British Columbia’s worst-ever wildfire season, Dr. Sarah Henderson began to receive worried messages from the families and friends of people with dementia.

“They were telling us, ‘My dad has Alzheimer’s, and he seems more confused than usual,’” she recalls. “The stories were coming from all over. At first, we weren’t sure what to make of them.”

A professor at the UBC School of Population and Public Health (SPPH) and Scientific Director of Environmental Health at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC), Dr. Henderson is a leading expert on the health effects of air pollution, extreme heat and other climate-sensitive hazards in the province.

But this was something new. Could wildfire smoke affect cognitive function?

She reached out to Dr. Chris Carlsten, the director of UBC’s Air Pollution Exposure Laboratory (APEL) and a close colleague, for his opinion. Dr. Carlsten agreed it was possible, and not just in people with dementia.

“The thing about air pollution — whether it’s wildfire smoke or ozone pollution emitted by vehicles and factories — is that it affects basically every organ system in the body,” he explains.

“Climate change forces us to confront existing health inequities and think very hard and very creatively about how we can build a healthier and more equitable future for everyone.”

– Dr. Michael Brauer

As global temperatures rise, and climate hazards intensify, so does their toll on our physical and mental health. We experience more severe respiratory illnesses, worse cardiovascular disease, and increased anxiety and distress from the uncertainty that comes with disruption — as well as other issues we’re only just beginning to understand. These effects are further compounded by where we live, how much money we make, whether we belong to a marginalized community and other factors.

“The fact is, we can’t separate our health from the social and physical spaces we inhabit,” says UBC’s Dr. Michael Brauer, a leading global expert on environmental health and frequent collaborator with Drs. Henderson and Carlsten.

“That’s what makes climate change such a multi-faceted threat — one that requires far-reaching, even radical solutions.”

Together, Faculty of Medicine researchers are investigating how everything from our genes, to the design of our cities, to the geography of extreme weather events can interact to make us more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Working in close collaboration with B.C. health authorities and colleagues around the world, they are translating this work into new tools and strategies to help protect our health, today and in the future.

It’s within this larger program of action-oriented research that Drs. Henderson and Carlsten set out to solve the puzzle of air pollution and brain health.

From DNA to demographics

Working with researchers from the University of Victoria, Dr. Carlsten designed a study that would map the neurological effects of air pollution. The team exposed 25 healthy adults to diesel exhaust for brief intervals in APEL’s state-of-the-art exposure booth, measuring brain activity before and after with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

They discovered that even brief exposure — equivalent to a commuter sitting in busy traffic for a couple of hours on a high-pollution day — causes a temporary dip in the brain’s default mode network, the circuit of interconnected brain regions which plays an important role in memory and thinking.

“This research, the first of its kind in the world, provides fresh evidence supporting a connection between air pollution and cognitive function,” Dr. Carlsten says. “The next step is to determine whether the mechanism is similar to what we see happening in the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, whereby exposure triggers an unhealthy inflammatory response at the cellular level.”

The study, published this winter, joins a growing and influential body of UBC research into the physiological effects of air pollution. In just the past few years, Dr. Carlsten and APEL scientists have demonstrated a definitive link between traffic pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); revealed how genetics make some people more susceptible to exposure-related health complications; and catalogued the epigenetic changes that air pollution can trigger in the human genome.

Clinical studies like these help to inform Dr. Henderson’s work. In her joint UBC and BCCDC roles, she takes a broader approach to the problem of climate-sensitive hazards and their impact on health.

“I’m a generalist in the sense that my research is oriented toward public health and how climate change affects whole communities and populations. When I need in-depth insights into the individual and physiological impacts, I turn to people like Chris,” she says.

Inspired by their conversation, Dr. Henderson embarked on a population-level investigation of wildfire smoke and brain function. She and her team analyzed the performance scores of 10,000 anonymous adult users of a popular brain-training app. All the participants lived in areas where there was recent wildfire activity.

The team found that poorer air quality correlated with lower scores — a proxy measure of cognitive function — in the short- and long-term, depending on the length of exposure.

Significantly, young adults and people over 70 showed the most pronounced effects. These demographic indicators are important, because the impacts of climate change are distributed unevenly within and across populations. Understanding who is most vulnerable, and why, is an essential part of Dr. Henderson’s work.

In two other studies, on extreme heat, she found that poverty, social isolation, and health conditions such as schizophrenia increase British Columbians’ risk of serious health complications and death during periods of high temperatures.

“Income, age, gender, education, social marginalization and pre-existing medical conditions — all of these things influence our risk for adverse health effects from climate hazards,” she says.

As it turns out, so does our immediate physical environment.

“The difference can be life or death”

For people who live in cities, the presence in their neighbourhoods of busy roads, multi-storey buildings, parks, community centres and good quality housing all affect their climate risk — and their ability to adapt.

“You can have two neighbourhoods side by side, one with heat-efficient housing, ample greenspace and shared public spaces, the other without. During a heat dome, like the one we saw here in 2021, the people in the second neighbourhood will, on average, fare worse,” says Dr. Brauer, a professor in the School of Population and Public Health.

“The difference can be life or death.”

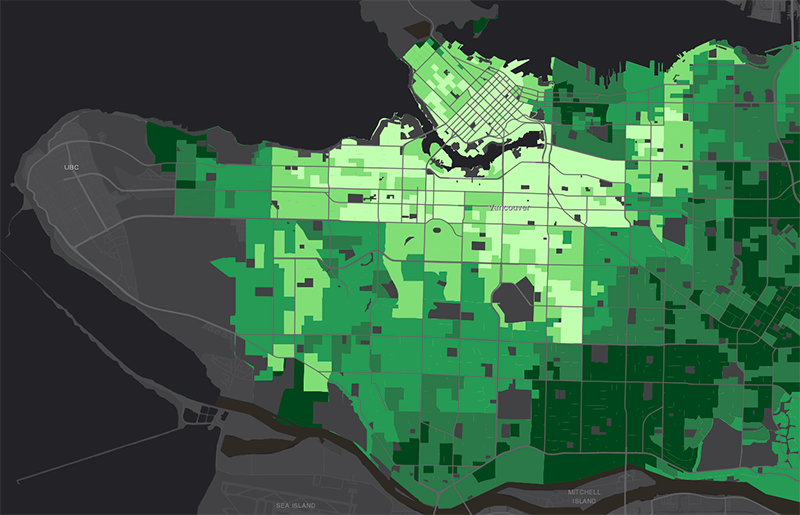

Working in partnership with regional health authorities, Dr. Brauer created the Climate Vulnerability Index, a powerful data visualization tool that allows researchers and policymakers to map the interaction between biological, social, and environmental factors and understand how they put certain neighbourhoods and communities at higher risk than others.

Users can explore maps of B.C.’s Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley, toggling between three different views. The first view shows a given area’s exposure risk to extreme heat, wildfire smoke, ozone pollution and flooding (measured by, for example, maximum summertime temperatures), while the second shows residents’ sensitivity to each hazard (measured by median age, prevalence of pre-existing health conditions, and so on). The third level shows their ability to adapt to the hazard (measured by income, education and access to social supports).

The result, when you combine all three views, is a vivid picture of climate vulnerability.

Practical interventions

As researchers better understand these interactions, potential solutions begin to emerge.

“If we know, for example, that older adults are among the most physically susceptible to extreme heat, and poverty and social isolation further increase their risk, then we can begin to look at specific ways of reducing their exposure and mitigating the impact,” Dr. Henderson says. “The same would be true for air pollution and brain health — or any climate hazard.”

Much of the research happening at the Faculty of Medicine focuses on practical interventions that can be implemented at the household, neighbourhood and community levels — and tailored to the circumstances of people who are most vulnerable. This includes strengthening social support networks, testing the protective benefits of anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative foods, designing more effective emergency alert systems and developing strategies for healthier aging in a changing climate.

“Income, age, gender, education, social marginalization and pre-existing medical conditions — all of these things influence our risk for adverse health effects from climate change.”

– Dr. Sarah Henderson

The research is also highly collaborative. Dr. Brauer is working with UBC’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the Department of Mechanical Engineering to rethink the way we design indoor spaces, making them easier to cool and better at filtering air pollution from outside.

Dr. Carlsten, who also directs the Legacy for Airway Health at Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and Forestry professor Dr. Lorien Nesbitt recently launched the Climate Change Health Effects, Adaptation and Resilience Network (HEAL). The HEAL research cluster brings together scientists from Medicine, Forestry and other disciplines to study the compounding health effects of extreme weather events and develop adaptation strategies for individuals and communities.

Medicine-Forestry collaborations have already yielded important insights into the protective benefits of urban greenspace on neurodevelopment in children and on mental health and dementia in adults.

Many projects are global in scope. Through the Healthy Cities initiative, UBC researchers are tackling urban health inequality in the context of climate change with partners around the world. Meanwhile, Dr. Brauer’s Global Burden of Disease-Major Air Pollution Sources Project is the most comprehensive study of its kind, ever, on global air pollution and disease — and publicly available as an interactive tool for researchers and public health officials.

“Just as we’re identifying places in B.C. where people are most at risk, we’re identifying those places around the world and making the argument that governments need to strategically prioritize those populations,” Dr. Brauer says.

Building a healthier and more equitable future — for everyone

With global temperatures projected to rise for the foreseeable future, the work of UBC researchers has never been more urgent. Or more forward-looking.

Dr. Henderson is teaming up with scientists from the Faculty of Medicine’s Edwin S.H. Leong Centre for Healthy Aging to study how wildfire smoke exposure during pregnancy rewrites infants’ biological markers of aging.

“We want to understand how wildfire smoke changes the way we age, beginning even before we’re born, what this could mean for our long-term health, and what the implications could be for future health policy,” she explains.

Dr. Carlsten, meanwhile, sees the potential for genomics to make public health interventions more effective: “If we have robust data which show that a certain percentage of the population is genetically more susceptible to air pollution, then we can use that data to drive public health measures,” he says.

Given the enormity of the challenge and the limitations of health resources in Canada and around the world, innovative solutions like these are needed.

“Through our research, we’re making the argument that governments need to strategically prioritize at-risk populations here at home and around the world.”

– Dr. Michael Brauer

But, as Dr. Brauer points out, we will only succeed if our efforts begin with the most vulnerable people. In this, he sees an opportunity.

“The silver lining, if there is one, is that climate change forces us to confront existing health inequities and think very hard and very creatively about how we can build a healthier and more equitable future for everyone.”

Better respiratory health for Indigenous communities

Indigenous people in B.C. experience higher rates of asthma, COPD, and other respiratory diseases. A team of UBC-VCH researchers is on mission to understand why — before climate change makes the problem worse.

A diet for healthier lungs and a healthier planet

UBC researchers are testing a secret weapon in the fight against air pollution: food!

Never miss an issue of Pathways

Pathways — the UBC Faculty of Medicine’s digital magazine — features stories about cutting-edge health education, breakthrough research, and biomedical innovations that are making a difference in British Columbia and around the world. Discover the impact of our people and programs.